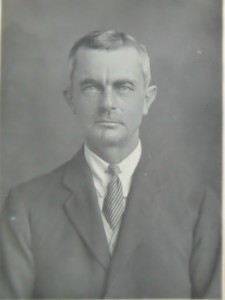

Douglas, the fifth of Lewis and Mary’s ten children, was born in 1876. With the other children—six boys and four girls—he ran around Pen Rhiw, with its extensive gardens, two tennis courts, wild rocky areas and plentiful servants, their father being largely away or absorbed in his work. He went to England at age 8, entered Reading School with two elder brothers, and then went to Connellan College in Malvern where four of the boys now studied. Three went on with him when the Headmaster moved to Yorkshire.

Douglas, the fifth of Lewis and Mary’s ten children, was born in 1876. With the other children—six boys and four girls—he ran around Pen Rhiw, with its extensive gardens, two tennis courts, wild rocky areas and plentiful servants, their father being largely away or absorbed in his work. He went to England at age 8, entered Reading School with two elder brothers, and then went to Connellan College in Malvern where four of the boys now studied. Three went on with him when the Headmaster moved to Yorkshire.

In 1892 Lewis and Mary came home and took the children away from the Yorkshire school, where they were not happy. Douglas was sent to King’s College, London, to study Civil Engineering, living with his Garrett grandparents in Hampton Hill, Richmond-on-Thames. Just as he was about to complete his three years and the examinations were starting, he received a cable from his father who had secured a post for him in the Mysore Government. He left immediately, and in 1895 joined the Public Works Department at the bottom.

So began his adventurous life, riding round his area–initially Mudgere, a sub-division of the Kadur district–surveying, clearing landslides, building roads and railways, usually in inhospitable places, and punctuating his work with horrifying incidents with panthers, tigers, elephants and snakes.

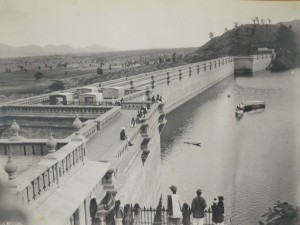

After a brief and unsuccessful period in America, where it was intended he should learn electrical engineering, and a spell in the Madras area at Madura, Douglas returned in 1898 with a good offer from the Mysore Government to work at the Mari Kanave Dam project under the brilliant engineer C. T. Dalal. The making of this huge dam created a lake that was in its time the largest man-made lake in the world.

‘Most of the labour was recruited from the Madras and Mahratta country and they had to be paid advance in money before they would leave their homes. The work proceeded well until a terrible catastrophe intervened. This was an outbreak of cholera, contracted by work-people drinking water from the river which was contaminated from a village higher up, where cholera was rampant. About 300 people died from the disease, and the whole lot—nearly 5,000 in number—decamped and left for their villages. Many of them left their dead and dying in the huts when they went and the place was overrun with pi-dogs and hyenas and vultures, and I witnessed many a gruesome sight….

‘At one corner of the dam site was a very sacred Temple dedicated to the goddess Mariamma, the goddess responsible for all catastrophes. The local people would have it that the dam would breach and the whole scheme prove a failure unless a human sacrifice was made to propitiate the goddess. I could do a great deal, but I could not deliberately offer up a human sacrifice. However, the difficulty was solved when a man was sucked through the temporary sluice we built in the foot of the dam to pass the floods. He came out dead and this was apparently accepted as sufficient to appease the goddess….

‘I got on very well with the work-people—they called me their Father and Mother!’

‘I got on very well with the work-people—they called me their Father and Mother!’

‘I had a number of serious accidents at Mari Kanave. In one I was run over on an inclined tramway I built for the supply of stone to the dam, owing to my own stupidity. I was caught on the incline by three empty wagons, which had broken loose, weighing 500lb. each. They all went over my leg and turned me over on my back. I was extricated unconscious and was being carried to my bungalow. I regained consciousness, got to my feet and hobbled along with my arms around the shoulders of two men. I went to bed with a crushed leg and other injuries. The man in charge of the dispensary wired news of the accident to the Chief Engineer in Bangalore, saying, “Mr Rice run over on railway line and suffering from deep crevices on leg and other injuries”; however, I soon recovered and resumed work.’

Douglas clearly loved all aspects of the work at Marikanave, and such leisure as there was too. He must have been one of the first drivers in the area, buying a single cylinder De Dion, perhaps around 1903.

After Mari Kanave, now called Vani Vilasa Sagara after the Maharani Regent of Mysore from 1896-1902, Douglas had various short-term jobs in the Kadur and Hassan Districts, and then on works associated with an iron and steel works, at the Cauvery Power Scheme and at the Kolar Gold Mines.

In 1911 he went home for eight months, in which time he became engaged to Phyllis Maitland Webb, a girl from Hatch End near Harrow. Douglas returned to India, and in 1912 his fiancée and her mother went out to Colombo in Ceylon for the wedding. On their return, the couple went to Mysore where Douglas rented a house belonging to a relative of the Maharaja which had 28 rooms and a garden.

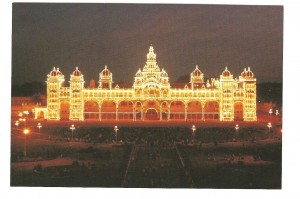

Douglas surveyed and constructed the railway line from Mysore to Arsikere, 80 miles with three bridges. He also had to supervise the building of the Lalithadri Mansion, a guest house for visitors to Mysore and now a very superior hotel. He was responsible for the maintenance of the Maharaja’s Fernhill palace with five bungalows at Ooty, and the huge palace in Mysore, where, as he remarks, ‘there was always something to do’. Nearly 100,000 light bulbs were, and still are, fixed to the outside of the building.

Douglas surveyed and constructed the railway line from Mysore to Arsikere, 80 miles with three bridges. He also had to supervise the building of the Lalithadri Mansion, a guest house for visitors to Mysore and now a very superior hotel. He was responsible for the maintenance of the Maharaja’s Fernhill palace with five bungalows at Ooty, and the huge palace in Mysore, where, as he remarks, ‘there was always something to do’. Nearly 100,000 light bulbs were, and still are, fixed to the outside of the building.

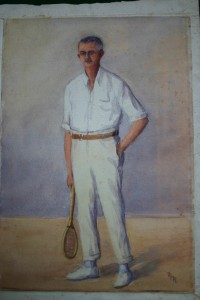

Douglas was a friend and sporting companion of the Maharaja, His Highness Sri Krishmaraja Wadiyar IV, ‘an orthodox Hindu who was held in the highest esteem’ The Maharaja had succeeded his father in 1894, but until 1902 his mother acted as regent. It was this lady, Vani Vilasa, after whom the lake at Mari Kanave was named.

Near Mysore City there is a hill called Chamundi, with a famous temple at the summit. In those days pilgrims had to walk 2,000 steps to the summit or take a circuitous footpath. ‘One day, when I was playing tennis with the Maharaja, I enquired why he had never had a good motoring road made to the top. He replied that that had been his great ambition for many years, but all his engineers had said it was not feasible.’

Douglas planned and executed the road. Halfway up, where he made a circular space with an island in the centre, from which a wonderful view could be seen, the Maharaja had a placard placed, reading ‘The Douglas Rice Circle’.

Douglas planned and executed the road. Halfway up, where he made a circular space with an island in the centre, from which a wonderful view could be seen, the Maharaja had a placard placed, reading ‘The Douglas Rice Circle’.

In 1916 Douglas was transferred to Bangalore, the headquarters of the Mysore State government. He surveyed a railway to the famous Jog Falls, and another down the Western Ghats to Bhaktal, where he produced a scheme for a harbour, which Mysore so far did not possess.

In 1918, Douglas and Phyllis lost their eldest son. They returned to England with their second boy. Douglas returned to India in 1920 and was promoted Chief Engineer for Roads and Buildings. Another son was born in the same year; not surprisingly his wife appealed to Douglas to return for good, so he retired in 1924 after nearly 30 years’ service

Immediately he was offered the job of General Manager of the Big Six in the Amusement Park at the Wembley Empire Exhibition. He writes that life was ‘a perfect nightmare of worry and anxiety, but I stuck it.’ The following year, 1925, Phyllis died; they had only been married twelve years. The Mysore Government now reappointed Douglas as Buying and Selling Agent in England, both to the Mysore Government and to the Maharaja. He later became Assistant Trade Commissioner. Among his duties was selling wild animals from India and buying horses, including a sacred one, for His Highness.

In his work he had to deal with orders from Mysore ‘of every conceivable kind’, but the main activity was the selling of sandalwood oil, made in Mysore State.

A new business Douglas started was the importing of granite kerb stones, which sold more cheaply than Scottish or Cornish stones. He got Mysore kerbs laid in many places in London and the suburbs, and even in Trafalgar Square. The business ended when war broke out, as shipping could not be spared.

Douglas also had to meet the many demands made by the Maharaja’s visit to London in 1936. ‘He came with a considerable retinue and stayed at the Dorchester, where a special kitchen was adapted as he had brought his own cooks and much of his food. He was keen to see race course, stables, kennels, poultry farms, etc…Wherever we went he bought what he fancied…I must have sent him quite ten different breeds of dogs—a pair of each—besides pigs, poultry, pheasants, etc.’

Douglas also had to meet the many demands made by the Maharaja’s visit to London in 1936. ‘He came with a considerable retinue and stayed at the Dorchester, where a special kitchen was adapted as he had brought his own cooks and much of his food. He was keen to see race course, stables, kennels, poultry farms, etc…Wherever we went he bought what he fancied…I must have sent him quite ten different breeds of dogs—a pair of each—besides pigs, poultry, pheasants, etc.’

Douglas retired from the Mysore office in Trafalgar Square in 1937, a hundred years after Benjamin arrived in India. He immediately went back, ‘to thank the Maharaja for all he had done for me and to see old friends.’ He was welcomed as a state guest in Bangalore and Mysore.

Douglas moved to a small flat in a large block, Elm Park Court, in Pinner in 1938, relying for transport on railway and bicycle. He was now in full-time work in Civil Defence.

In the next years Douglas did several other jobs—Post and Telegraph Censorship, on the panel of lecturers at the War Office for the education of His Majesty’s Forces, the Post Office Savings Bank—but he retained his connections with India. He carried out a surveying job on a house in Hertfordshire for the Maharaja’s Private Secretary, and in 1944 acted as agent for the Dewan of Jaipur in the purchase of steam turbo generating plant. He entertained groups of all kind with his slide lectures on his life in India.

When he completed his autobiography, in 1951, he had been a widower for 26 years. He wrote: ‘When I recall my life in India, I shudder to think of the awful risks I took so lightheartedly, and realise how fortunate I have been to come out of it all with a whole skin. I have had a most interesting life, with great responsibilities at times.’

Douglas died in London in 1959 at the age of 83.