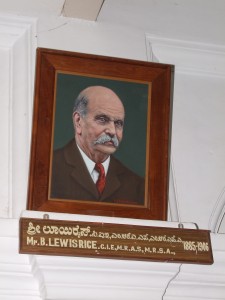

Lewis was born in 1837 and grew up in Bangalore. For him and his siblings, India was home; in their early years they spoke the native languages more freely than English. Lewis went to an apparently well-known school in London run by Rev. Alexander Stewart and his sons. Clearly he was a success there, and was kept on, after completing his studies, as an assistant teacher for a year or two.

Lewis was born in 1837 and grew up in Bangalore. For him and his siblings, India was home; in their early years they spoke the native languages more freely than English. Lewis went to an apparently well-known school in London run by Rev. Alexander Stewart and his sons. Clearly he was a success there, and was kept on, after completing his studies, as an assistant teacher for a year or two.

When his parents arrived in England on leave in 1853, he learned that though his father knew Lewis ought to go to University, he could not afford to send him there. Lewis decided to make himself independent, and worked in a foreign merchant’s office and then in the office of an American bank. Meanwhile he was preparing for the Indian Civil Service examinations, but happily at this moment he was offered through an old family friend, Mr Garrett in Bangalore, the post of Principal of the new Bangalore High School. He left England in 1860, taking up his new post at the age of 23.

The school at first held about 200 boys with six assistant masters, of whom four were natives; during Lewis’s six years as Principal, it flourished and expanded. Lewis introduced recitations, theatrical performances and debating. The aim was evidently to prepare students for entry to Madras University. The High School continued to increase and became a showpiece for visitors.

But Lewis was glad to be appointed Inspector of Schools, taking up the job in 1866, as he could now range freely on horseback over the whole province of Mysore. He gained an intimate knowledge of the State and appreciated its historic interest. After only two year as Inspector, Lewis found himself Acting Director of Public Instruction for Mr John Garrett, who went on leave.

A major aspect of Lewis’s work was the organisation of a huge extension to the indigenous schools called the Hobli system. It was necessary to produce buildings, books and training for teachers in each of 645 hoblis or areas. Lewis made a tour of the whole Province in order to carry out this work. During this time he must also have been writing what appears to be his first published work, An Introduction to Sanskrit (1868).

After 10 years service Lewis was now due for home leave. He arrived in England in June 1869, and was married the next month to Mary Sophia Garrett, the daughter of John Garrett, to whom he had been engaged in India for over eighteen months. After essentially a year-long honeymoon in Europe, Mary and Lewis returned in June 1870 to Bangalore, ‘very thankful to be home again’. They took a house near the Palace entrance, and here the first of their ten children was born.

Soon two important events occurred: firstly a Major Dixon showed Lewis some pictures of the many inscriptions in stone in the area, asking him to provide a translation. This was the beginning of Lewis’s connection with Archaeology. Secondly, in 1873 Lewis bought a plot of land on the High Ground on which he built a house which he called Pen Rhiw (Welsh for ‘top of the hill’).

It still stands, a comfortable, airy house in a large garden. It has been the residence of the Cobra beer magnate and also of executives of an oil company, and is now the home of a clothes and fashion boutique.

It still stands, a comfortable, airy house in a large garden. It has been the residence of the Cobra beer magnate and also of executives of an oil company, and is now the home of a clothes and fashion boutique.

In the same year, 1873, Lewis was also appointed to compile the Gazetteers of Mysore and Coorg, the area to the south-west of Mysore. These weighty books, official summaries of all aspects of the States, were published four years later, and were well received. On the retirement of his father-in-law, Lewis was appointed Director of Public Instruction in both areas.

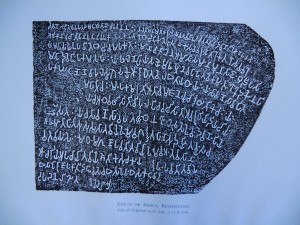

In 1879 was published his ‘Mysore Inscriptions’ containing all Major Dixon had photographed: this ‘opened the eyes of scholars to the valuable records in Mysore’. Lewis was thus the first person to transcribe, transliterate, translate, publish and comment on the thousands of stone inscriptions in Mysore state. They date from 300 BC to the nineteenth century, and are in Sanskrit, Kannada and Tamil. They may be statements of laws or principles of government, prayers, commemorative pieces or poetry. Lewis created a new kind of study which he called epigraphy; he himself (with his team of local scholars) published 9000 of the inscriptions. Since that time the study has continued, and at least a further 10,000 have been published. Epigraphy at Universities forms part of the subject Archaeology.

Lewis used to ink the inscription, and press soft paper to the stone. He would take the imprint back to his office, and with the aid of his munshis—local experts—would transliterate and translate the text.

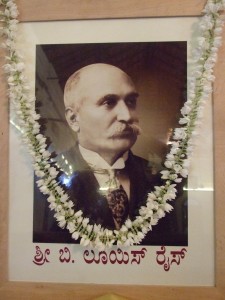

Lewis’s great contribution to Mysore was to realise the significance of these inscriptions and make them public. In a country where scholarship is revered, Lewis is regarded as the founder of a new archaeological discipline.

After a year’s leave in England in 1879 and a short spell working for the Indian Education Commission in Calcutta, Lewis became Secretary to the Government of Mysore in the Education and Miscellaneous Departments and in 1884 Director of Archaeological Researches. In the same year he was appointed C.I.E.

He modestly states that ‘I had by that time published a Report on the 1881 Census. Also a Catalogue of the Sanskrit Manuscripts in Mysore and Coorg: and the Karnataka Bhasha Bhushana, one of the most ancient grammars of the language, never before printed. To this I prefixed an account of Kannada Literature, as far as then known.’

In 1889 Lewis published a volume on the inscriptions at Sravana Belagola. He records that this created great interest because it contained much new material on the then little-known sect of the Jains. It led to Lewis being set to work on all the inscriptions in the State.

But it was at Chitaldroog, to the north of Bangalore, that Lewis made the discovery he regarded as his crowning achievement. In 1892 he found three inscriptions inscribed in rocks, carrying the same text of an Edict of Asoka.

Asoka (or Ashoka) the Great was perhaps most remarkable man ever to rule India. Beginning as a Hindu, and himself a warmaker, he was changed by witnessing the mass deaths resulting from his desire for conquest. Converting to Buddhism, he spread its principles throughout his vast empire—between about 269 and 232 BCE he ruled almost all of the Indian subcontinent. Renowned as a philanthropic administrator, he was devoted to non-violence, love, truth, tolerance and vegetarianism.

Asoka (or Ashoka) the Great was perhaps most remarkable man ever to rule India. Beginning as a Hindu, and himself a warmaker, he was changed by witnessing the mass deaths resulting from his desire for conquest. Converting to Buddhism, he spread its principles throughout his vast empire—between about 269 and 232 BCE he ruled almost all of the Indian subcontinent. Renowned as a philanthropic administrator, he was devoted to non-violence, love, truth, tolerance and vegetarianism.

The inscriptions are solid evidence of the extent of his influence. They date from the third century BCE, and no earlier inscriptions have come to light anywhere in India.

The Edicts are written in Prakrit, the language of the common people, and their main object, Lewis tells us, is ‘to exhort all classes to greater effort in pious duties. In doing this the king adduces his own example, how while he was a [Buddhist] lay disciple he did not exert himself strenuously, but after he entered the Order he did so.’

The Edicts of Asoka were his most glamorous discovery, but Lewis made many other important contributions to learning. One was the collection, as he went on his tours, of palm-leaf documents, the usual form written documents took in earlier times.

Lewis had many adventures during his travels through the countryside. One note he calls A Spirit’s Revenge: ‘At one place we were making copies of an inscription on a stone the lower portion of which was buried in the ground. No one could be got to dig round the bottom, all being afraid of evil spirits if it was interfered with. The shekdar, a Brahman, was so annoyed he said he would dig it up himself. Ashamed at this, a young villager came forward and offered, with much trembling, to do it. He seized hold of a pickaxe in a flurry to make the first stroke, but owing to his agitation, in lifting it up to dig he struck his forehead with the point, inflicting a wound. With an unearthly yell he dropped the pickaxe and bolted as hard as he could run. Every one regarded it as a righteous judgment and were confirmed in their old beliefs.’

Between 1886 and 1906 Lewis spent half the year touring and half editing the results of his findings. He published twelve volumes of Epigraphia Carnatica, covering the whole State. The volumes include nearly 9,000 inscriptions. In 1906, before retiring, he completed the six volumes of Bibliotheca Carnatica, a collection of all the major literary texts, in Kannada, Sanskrit and other languages.

Between 1886 and 1906 Lewis spent half the year touring and half editing the results of his findings. He published twelve volumes of Epigraphia Carnatica, covering the whole State. The volumes include nearly 9,000 inscriptions. In 1906, before retiring, he completed the six volumes of Bibliotheca Carnatica, a collection of all the major literary texts, in Kannada, Sanskrit and other languages.

In May 1906 Lewis retired to England, living in a new house he built in Harrow. He continued to work in various academic capacities, researching, bringing out new and extended editions of his earlier works and contributing to learned journals and societies. He and Mary celebrated their golden wedding in 1919 at their home.

Lewis died on 10 July 1927, aged a week under 90 years. The Mythic Society Quarterly Journal (1927, p 19) carried an obituary which said that ‘People of Mysore feel a personal loss’ in his death. ‘The present position of Kannada literature and our knowledge of Mysore history are almost entirely due to his labours.’

Lewis’s brothers and sisters

It is perhaps not surprising that Lewis’s two sisters and three brothers all stayed in India for much of their working lives.

Jane married Robert Paton, an engineer on the Madras Railway and Great Indian Peninsular Railway; Eliza married in 1861 Rev Alec or Alexander Blake, a missionary with the Free Church of Scotland in Madras; James also was an engineer on the GIP Railway and South India Railway, and seems to have been Chief Engineer for Madras in about 1897. Henry and Edward were both, like their father, missionaries in South India.